Blass from the Past

It was a scene right out of a Disney movie. The plaza in front of the Canaan Union Depot was crammed with people, an overflow crowd spreading across the lawn of the Episcopal church across the road. Bands played and flags fluttered in the fall breeze as a parade made its way toward the plaza.

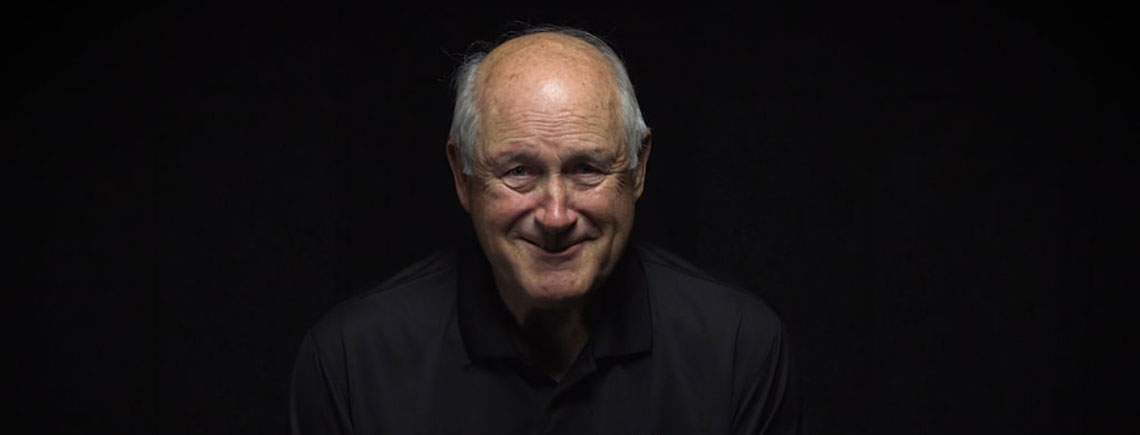

The object of all this attention was a lanky young man from Falls Village who had just days before pitched two games in the 1971 World Series, propelling the Pittsburgh Pirates to an unexpected championship. Steve Blass was returning home to the Northwest Corner, the undisputed hero of the day.

His crowning achievement took place 52 years ago yesterday, on September 17th, when he pitched all nine innings in the seventh game of the series, a record that has not been matched since.

As he recounted the event for an Amazing Tales podcast, “I got into this bubble, I was always three pitches ahead in my mind. We are taught and developed to block out the enormity of the situation but when I look back I think, ‘My God, I grew up in Falls Village with a population of about 1,100 people and I was going to pitch in the World Series with 50,000 people watching everything I did and millions more on television. Every once and a while, late at night over a glass of wine I think, ‘How about that—a kid from Falls Village performing like that.’”

This Field of Dreams story began in Canaan. “I grew up in Canaan and Falls Village,” he said. “It was kind of a Norman Rockwell setting. The first field I played on was behind the State Police Barracks. I was 8 years old and dazzled. Some of the 12-year-olds on the team were already shaving—that how old they appeared to me.”

Later the playing field—today named for him—was moved to a spot near the new elementary school. “At that time, it was on a slope to the point you had to run uphill to first base,” he recalled with a laugh. “It was a wonderful time. It was a time in life when you had your breakfast and your mom said, ‘Be home for dinner.’ If you had a bicycle, you felt like you owned your town. It was a great time to grow up there and great place to grow up.”

More an athlete than a scholar, Blass grew up with a ball always in his hand. “When school recessed (for the summer), the first thing I did in the morning was to run to the window to see if the weather was good enough to play ball.”

But even though he began to draw attention as a pitcher while still in the Little League and Babe Ruth Leagues, his career was put on hold when he reached Housatonic Valley Regional High School where he had to wait his turn behind a cadre of super talented pitchers coached by legendary coach Edward Kirby.

The pitchers, brothers Peter, Art and John Lamb from Sharon and their cousin, Tom Parsons of Salisbury were all scouted by the Pittsburgh Pirates and three of them signed contracts and wore Pirates uniforms (Peter decided to go on to college). Ironically young Steve Blass would become part of this extended family when he married the Lamb’s sister, Karen.

“I had to wait my turn on the varsity team because there was so much talent,” he said. “In grammar school I got to have little bit of a name for myself because I could throw hard. I had to go from that to high school where I had no reputation at all. All those guys were ahead of me.”

“Art had the best stuff of all of us but blew his arm out,” he continued. “Tom played for Pittsburgh and the Mets.”

And John Lamb also wore a Pittsburgh uniform but suffered a fractured skull in 1971 when he as hit by a line drive during spring training. He collapsed on the mound and later underwent surgery that put him out of action for much of the season and stalled his career.

Blass reported that baseball scouts were acutely aware of Housatonic Valley Regional High School because of this cadre of talented youngsters and this ensured that they came to Falls Village to check out his potential. He signed with the Pittsburgh Pirates in 1960, made his major league debut at the age of 22 in 1964 and joined the team permanently in 1966. Blass was one of the National League's top pitchers between 1968 and 1972, helping the Pirates win four National League Eastern Division titles in five years.

So it was as a seasoned veteran that took to the mound in the third and seventh games of the World Series. “I didn’t pitch until the third game of the series because I had my face ripped off in the playoffs,” he recounted. He explained that he tried to strike everyone out by throwing hard rather than following his successful performances during the regular season. By the series he decided to go back to his accustomed style.

“I was nervous,” he admitted. But despite his training to block out the enormity of the event, he allowed himself a moment to absorb it. “I said to myself, ‘I am so glad I have the presence to do this, I want to just take it all in. I took a visual walk around the stands. I got out of the bubble and said, ‘I may never have the opportunity to be in this situation again’—and I was right.”

He slipped back into the bubble and pitched the game of his life, a four-hitter that took Pittsburgh to the national championship. “At the top of the ninth, I just wanted to get out there and to see if I was good enough to do it. I went out and got them out—one, two, three.”

But not without a scare. The second batter was Hall of Famer Frank Robinson who had homered on a hanging slider in an earlier game. “My first pitch, the minute I let go of the ball, I saw it was going to hang. As the slider got to hi I looked up and said, ‘God, if you get me out of this, I will be a good Catholic boy the rest of my life.’ And he hit it straight up in the air. I don’t know about the promise ….”

He remembers his joy at seeing his father clambering over the dugout roof, determined to join his son on the field. “I see my dad, this plumber from Falls Village who was not going to be deterred from getting down on that field. It doesn’t get much better than that. It was rare air and I don’t take it lightly.”

Paradoxically, the height of his success eventually led to his career’s end. He suffered a sudden and inexplicable loss of control after the 1972 season. “Steve Blass Disease” has become part of the industry’s lexicon, describing the problem when talented players inexplicably and permanently seem to lose their ability to throw a baseball accurately. Blass retired in 1975.

But his career with Pittsburgh, a team to which he shows unwavering loyalty, was not over. He joined the Pirates' TV and radio broadcast team in 1983 as a part-time, earning a full-time post in 1986. Blass retired from broadcasting in 2019 after 60 years with the organization as a player and broadcaster.

He is in the Kinston Professional Baseball Hall of Fame, the Charleston WV Baseball Hall of Fame and was an inaugural member of the Pittsburgh Pirates Hall of Fame in 2022.

Blass still returns to his hometown from time to time to help local organizations. Most recently, he was a guest speaker at the Canaan-Falls Village Historical Society’s summer lecture series.