Cornwall Seasons

Curt Hanson had no further to look for inspiration than out the 16-foot windows of his Cornwall Hollow studio. There, the pastoral landscape stretched before his eye much as it had for generations past.

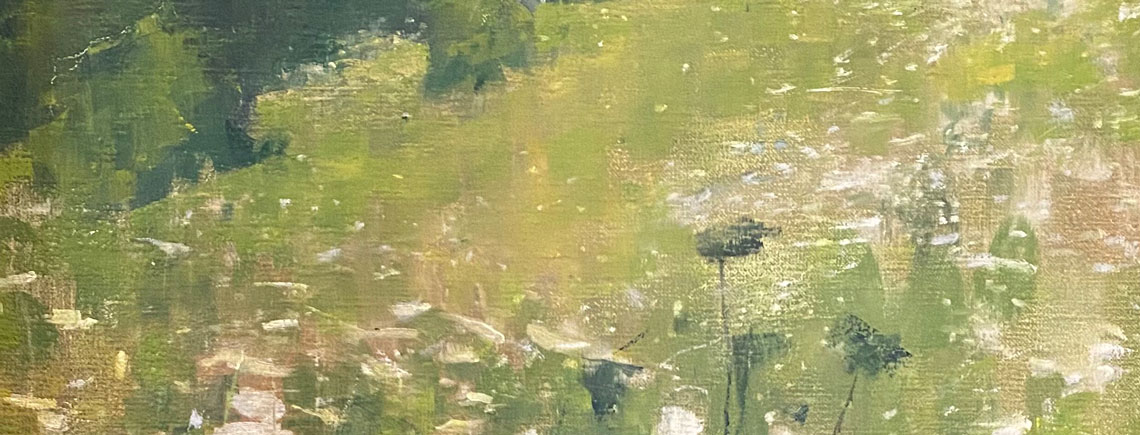

Cows in a field, water moving through the twists in the lazy Hollenbeck River, woodland interiors and the changing moods of the seasons were all subjects for his brush. Those seasons will be on display at the Cornwall Library through October 23rd in a show, titled Curt Hanson: Seasons in Cornwall.

Artists were first drawn to pastoral Western Connecticut in the late 19th century. Land was cheap as farms were abandoned for greener pastures in the West. Urban artists were able to relocate to the beautiful Northwest Hills and still find a ready market for their work as well-to-do city dwellers established second homes here.

Hanson, born in 1947 in Washington state, was a late-comer to this movement, not arriving in western Connecticut until 1979 and in Cornwall until 2001 where he purchased a vacant church. It was a perfect spot for the contemplative artist who, by all accounts, connected to nature from an early age.

Hanson found his way to Cornwall via a circuitous route. He studied art at Fort Wright College in Washington State with Charles Palmer and Stan Traft but it was perhaps the many fishing trips the three took together that cemented his ability to translate what he saw onto canvas. Following college, he made his way to New York City where he fell under the sway of the Barbizon School painters and especially the work of George Inness, known to some as “the father of American landscape painting.” So deep was Inness’ effect on the emerging artist that Hanson named his son Inness.

“Back in the early ’70s, I came across an essay and catalog by Robert Herbert which accompanied an exhibition called Barbizon Revisited, Hanson wrote. “I never saw the show and the reproductions in the little book were not very good but it caught my interest. It led to a growing interest in what is called ‘the Barbizon School’ and what later became referred to as Tonalist painting here in America. This basically set the course of my life work over the past 45 years. There is something about the somber, quiet mood of the Tonalist landscape that has never left me even though impressionism and open-air painting have had (their) effect on my development.”

Tonalism was a style that emerged in the 1880s when American artists began to paint landscapes characterized by soft, diffused light, muted tones and hazily outlined objects, all of which imbue the works with a strong sense of mood. Among its main exponents were Inness, James McNeill Whistler and Ben Foster.

Ironically, one of Hanson’s muses, Foster, worked in Cornwall Hollow 75 years before Hanson took up abode there. Foster’s tonalist palette, with its with subdued colors and limited tones—almost exclusively autumn colors, muted browns, grays and rusts—spoke to Hanson. In a biographical sketch, Hanson noted, Foster “worked right here and his motifs can still be seen here in the Hollow.”

First emulating the Barbizon painters in 19th-century France, Hanson was early known for painting en plein air, setting up outside and creating his work on site. He later evolved to working more in his studio, the method he used until his death in 2017.

He described his process thus: “Now, most of the work is done in the studio, beginning with thin transparent layers of tone and then a process of layering and scumbling and adding heavier paint if it is called for. It is not so much based on what is actually seen as I was doing when I was younger as it is a visual poem that may have reference to a particular view ...The purpose of the work is to convey a certain feeling. That feeling, in this case, is a quiet mood, a reflective mood, sometimes melancholy but with a sense of peace about it.”

And, at the end of his career, he no long felt a need to slavishly recreate what was before his eyes. “The decisions about what goes in, what is left out or when to leave off, comes more from the painting itself and not from the fleeting conditions of working directly from nature,” he wrote. “This is not to say that fine work cannot be done painting directly from nature, but there comes a point when it is time to step back and let the painting speak on its own terms. The purpose of the work is to convey a certain feeling.”

As his artistic technique evolved, so did his spirituality. He wintered in Thailand, married there and became a practicing Buddhist. He said he found his peace in the ever-changing seasons, his vegetable garden and his wife, Onwarin. Together, he said, they “provide me with all I need to live in harmony with nature. The paintings are a visual prayer that goes out to all sentient beings.”

Hanson’s work, which is for sale, can be viewed at the Cornwall Library, 30 Pine Street during regular opening hours: Tuesday, noon-5PM; Wednesday, noon-7PM; Thursday, noon-5PM, Friday, noon-6PM and Saturday, noon-2PM. The library phone is 860-672-6874.