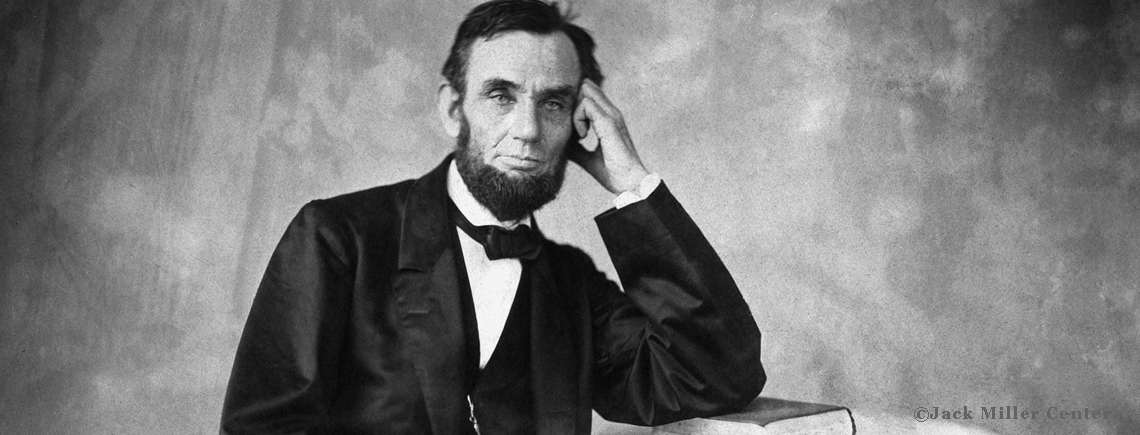

Lincoln's Legacy

February is a month with few redeeming merits. Only two spring to mind—first, it is short; second, it is the birth month of my favorite historical personage, Abraham Lincoln.

My fascination with Lincoln began early and has endured. I remember a shopping trip I took with a friend when I was 12 or 13. She was on a mission to buy new clothes and I wandered into an adjacent bookstore while she tried on outfits. Reunited, she asked what I had purchased and I produced a paperback history of Lincoln. “But you have already read a book about him,” she said.

I wonder what she would think if she wandered into my library today where at least three of my book shelves are dedicated to the great man. I have made multiple pilgrimages to worship at the altar of Lincoln in Illinois and have traced his family through Indiana and Kentucky, starting with the Kentucky farmstead where his grandfather, Abraham, was felled by an Indian arrow and ending with the stately home in Springfield Il where the increasingly affluent country lawyer was informed he would be the Republican candidate for president.

In his bicentennial year, I pledged to read only books about Lincoln. Being a slow reader, I managed to plow through only six or seven more of the estimated 15,000 books written about him but one of those was an impressive tome of recollections by those who knew him and his family in his early years. The memories, gathered by his long-time law partner, William Herndon, are the basis for virtually all that is known about his childhood and young adult years. They are raw, unvarnished accounts from people who were frequently uneducated and not always admiring. Reading them, it was interesting to see what historians have weeded out of the narrative as Lincoln passed from a living, breathing man to the pantheon of gods.

So, what fascinates me about this enigmatic, contradictory man?

Perhaps it is that he materialized out of nowhere. His father, who rented his strong son out by the day to earn money for the family, resented Abraham’s intellectual leanings. Thomas grudgingly sent him to “blab” schools from time to time—in all for less than a year—but it fell to his step-mother to protect Abraham from his father’s anger when he was discovered reading.

Lincoln lived on the fringes of civilization in his boyhood, in a one-room cabin where he passed evenings doing mathematical problems. Lacking paper and ink, he worked with a lump of charcoal on a wooden plank, shaving off each day’s studies with his pen knife to create a clean slate. He borrowed books anywhere he could find them, once estimating he had read every book in a 50-mile radius. In his own summation of his life, he wrote, “There was absolutely nothing to excite ambition for education.”

And, yet, here was a man who, already a self-made lawyer, taught himself Euclidean Geometry while riding the court circuit, “often studying far into the night with a candle near his pillow, while his fellow-lawyers, half a dozen in a room, filled the air with interminable snoring.” (Abraham Lincoln, 1860 Short Autobiography). He undertook the exercise, he said, to improve his powers of logic and language.

And, while he and close friends all admitted that he was not a quick study, he analyzed each new concept from every angle until he was fully satisfied that he understood it. His language was formed by his intimate knowledge of the Bible and through his devotion to Shakespeare and other poets. His sentences were burnished until they glowed—emotionally nuanced, legally precise, imbued with the moral righteousness of his parents’ “Hard Shell” Baptist ethic.

So eloquent were his writings that he was quoted frequently—by both sides—during the inaugural week just past, 156 years after his death. Interestingly, both modern parties have tried to claim the rough-hewn man from the frontier. The Republicans declaring themselves to be “the party of Lincoln,” try to usurp the moral excellency displayed by the 16th president while the Democrats echoed his words at least six times during the inaugural ceremony.

But the Republicans, now perhaps better called the party of Trump with their White Supremacist leanings, are the antithesis of Lincoln. Since the 1960s, they have traveled a long road that, as yet, has no turning, turning from Lincoln’s principles to embrace states’ rights and resistance to civil rights for African Americans. Lincoln might wonder why he fought the Civil War.

It is not the first time that political parties have slipped the moorings of their ideologies. Lincoln humorously described the inversion of party alignments in an 1859 letter to a Boston committee that had invited him to appear at a birthday celebration honoring Thomas Jefferson.

“I remember once being much amused at seeing two partially intoxicated men engage in a fight with their great-coats on, which fight, after a long, and rather harmless contest, ended in each having fought himself out of his own coat, and into that of the other,” he wrote. “If the two leading parties of this day are really identical with the two in the days of Jefferson and Adams, they have performed the same feat as the two drunken men.”

More than a century after the Civil War, our Republicans and Democrats seem to have achieved the same result. The parties have flipped on racial issues, with southern whites moving from the Democratic to the Republican party while the Democrats have attracted larger numbers of Blacks. Oddly, the Republicans, led by a billionaire, are seen as the party of the people, while the Democrats, with a self-made man at their helm and a large Black constituency, is labeled “elitist.”

Trump, to give him credit, has been true to himself. He is openly ambivalent about aligning himself with Lincoln. He wanted the luster of Lincoln’s memory tied to his own administration, but really didn’t like the man or his mission. In language neither as polished or as politic as Lincoln’s, Trump said after his 2016 election, “He was a man who was of great intelligence, which most presidents would be. But he was a man of great intelligence, but he was also a man that did something that was a very vital thing to do at that time. Ten years before or 20 years before, what he was doing would never have even been thought possible. So, he did something that was a very important thing to do, and especially at that time.”

Then he added that Lincoln “did some good,” but that his legacy is “always questionable.”

I doubt that Trump sits up late many nights doing Euclidean Geometry to hone his logic and language.

Joe Biden is not Lincoln. His rhetoric is not soaring. His mind and experience are pragmatic. But like Lincoln, he feels the pressure to bring his country back together, to restore respect and civility to the national dialogue.

Lincoln’s declared in his second inaugural address, "Let us strive on to finish the work we are in; to bind up the nation's wounds; to care for him who shall have borne the battle." Biden, less eloquently declares, “We must end this uncivil civil war” and borrows a phrase from Lincoln when he says “his whole soul” is in this endeavor.

I do not know if Biden can do it. But like “Honest Abe,” Biden is pledging to tell the truth, to accept that he will make mistakes and to ask for guidance, divine and human, when he errs. That, in my mind, is better than bombast, grandiosity and self-delusion. So, let us get on with it. Let us “bind up the nation’s wounds” and “strive to finish the work we are in.” Americans—all of us—deserve it.