An Elegant Icon

The Loss of New Hartford House

Styles change with the decades, even more with the centuries, but one thing never changes—the human desire to gather, to enjoy good times and good meals. For nearly three centuries, the New Hartford House was the social gathering place for area residents, home to a series of successful hostelries and soon to be the site of another.

“It was the place everyone went to celebrate,” said First Selectman Daniel Jerram, who himself took his wife to dinner there the night he asked her to marry him. “I had the ring in my pocket whole evening,” he related.

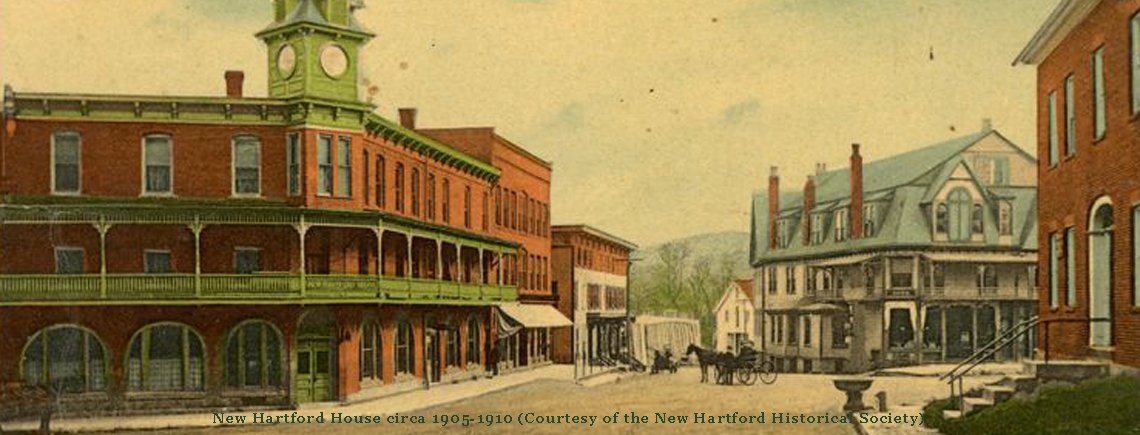

The loss of the venerable building to fire last week means it will never again fulfill that convivial purpose. The L-shaped building, with its graceful brick façade and second-floor balcony, was razed to the ground within 36 hours of the fire, literally leaving a hole in the life of the community.

“It seems so strange to look out my window and see blue sky,” said Town Clerk Debbie Ventre as she resumed work in the neighboring Town Hall last Thursday following a fire-imposed hiatus.

New Hartford Town Historian Emeritus David Krimmel said the corner of Bridge Street and Route 44 was probably occupied as early as 1738 by Martin Smith. Then, in 1759, Martin’s son, Seth, applied for a tavern license.

“The Colonial General Assembly required that there be a tavern about every 30 miles—which is about as far as you could travel in a day,” he said.

It is not clear whether a tavern was in continuous operation there before 1799, when the Greenwoods Highway, the prototype Route 44, was laid out. Theodore Cowles was issued a tavern license in 1800 and his probate records show a sizeable inventory of sheets, pillow cases and other items indicating that he ran a tavern.

The 1810 census records 23 persons living on the site; oddly, 22 persons were reported to occupy apartments in the much-enlarged building when it burned Tuesday.

Following Theodore’s death, Harry Cowles purchased “the tavern stand” and leased the “tavern house, wood house, barn, horse shed and part of one other barn and garden spot” to John Shepard for $550 a year.

In 1836, Harry Cowles placed an advertisement in a newspaper describing the property as “a two-story house, 68 by 30 feet, with a dry cellar and wing 44 by 28 feet, containing two dining rooms, each 26 by 14 feet; a large kitchen with fountains of pure water brought into the room; the remaining part being divided into large, pleasant and airy rooms.”

The corner lot must have been crowded with two 60-foot-long barns and a carriage house, as well as large wood shed.

“An opportunity is here offered to an enterprising man to make his fortune,” Cowles advertised, “or to capitalists for investment, there being no other Hotel in the place.”

“Early photos show a wooden structure,” said current historian Anne Hall. “The hotel has seen a lot of changes.”

By 1888, the old tavern was razed and a new section was attached to a neighboring building. The second-floor porch of the building on Main Street was extended along the side of the new structure to create a longer, continuous block. According to Hall, this building burned (to what extent is unknown) in 1897. Perhaps it was then that the brick façade was added.

Elias Howe, who on September 10th, 1846 was awarded the first patent for a sewing machine using a lock-stitch design, had a mechanic’s shop in the basement. A Handbook of New England, written in 1916 by Porter E. Sargent, states that “In Howe’s shop, on the site of the New Hartford House, woman first sewed a stitch on a sewing-machine.” Millions of women since have blessed his innovation.

So New Hartford House is a thing of the past. It remains to be seen what will happen to the corner of town that has witnessed so much history and enterprise.