Quilts with a Message

DARNstudio Celebrates Black Lives Matter

There is something comforting about a handmade quilt. Perhaps the mystique stems from the tradition of mothers and grandmothers, sitting in groups, forming patchworks of history from odds and ends of fabrics. Weathered and faded through the years, these works of art still hold great sentiment for us and carry memories of relatives long since gone.

In many cases these relics have been in the same families for many years.

Are there still quilting bees and gatherings? Perhaps in these days of a pandemic, women (and perhaps some men) are working on them alone, trying to maintain serenity while creating a piece of history for future generations. For some, the goal is even grander. Designers David Anthone and Ron Norsworthy have established DARNstudio for a dual purpose: to celebrate the creation of quilts and to further the Black Lives Matter movement.“ In 2017 we decided to start producing a cycle of quilts called Another Country,” explains Norsworthy.

A selection resulting from that collaboration is now on display at Five Points Gallery in Torrington which runs through December 20th, with a Virtual Artist Talk Friday, December 4th, at 6PM; www.fivepointsgallery.org.

“David had his own design firm and I had mine as well. It was a response to the injustice and what was occurring with Black Lives Matter. We wanted to create something meaningful and representational and bring attention to what was going on around us.”

Anthone and Norsworthy, who are spouses as well as business partners, decided to focus on the quilt—a quintessential example of home, contentment and safety. And they incorporated another nostalgic object, the matchbook, in the design.

Conceiving of the matchbook as a means of honoring the dead brought new meaning to the quilt project.

In the days when every restaurant offered a book of matches at the table, collecting them was a way of keeping memories alive – gatherings with friends and family to honor a birthday, a romantic dinner for two or a special celebration. For years many people collected these match covers in albums or in bowls on the table—a tangible symbol of times past.

“In general, with our process we are trying to apply new meaning, a re-meaning to something,” says Norsworthy. “Quilts are really loaded objects with all kinds of information. This idea of comfort and tradition and what the quilt is made of is always meaningful. But what if those different inputs were turned inside out? What would it mean to interrogate that idea of quilts as comfort? There are so many layers of meaning.”

“David and I try to broaden the topic so it can get to a lot of different audiences,” he continued. “We wanted to take the Country project a step further and decided to make quilts out of matchbooks, another definitive symbol. Instead of comfort, what is the opposite of comfort? To be a black man in this country is to always have that sense of discomfort. What it means for me is not necessarily what it means for David. It adds a level of interest to our work. We are always in conversation with the work as we create it and with each other. We each bring our own opinions and experiences to the table.”

“When we decided to create a different souvenir out of the matchbook,” explains Norsworthy. “By putting the location of where this victim was killed we turned the matchbook into a symbol, an announcement. It’s still a souvenir of a kind, but not in the way we have always interpreted a souvenir. It makes the people who look at the quilts see them in a different way. History is fluid and we are reminding people of that. We are making a strong connection between the Underground Railroad quilts of the mid-19th century and now. What does emancipation mean? What does Jim Crow mean? Where is Jim Crow today?”

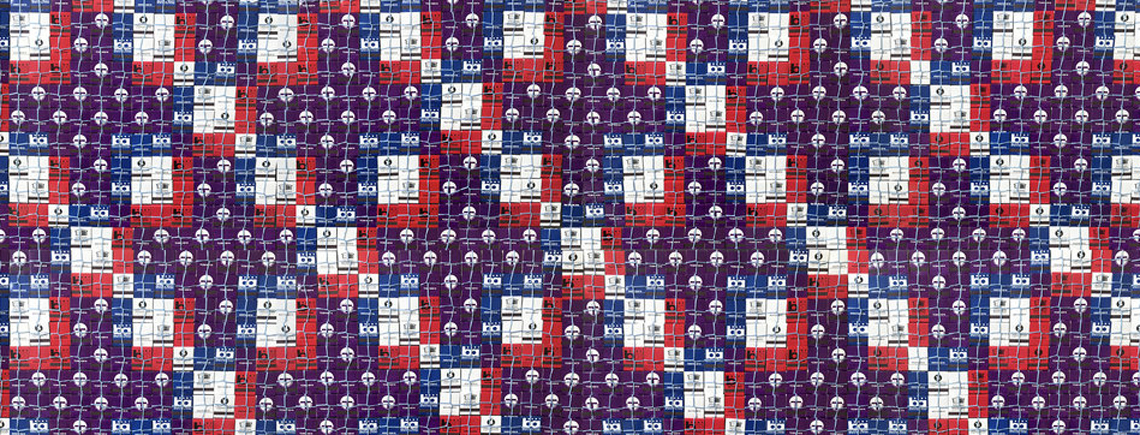

Norsworthy and Anthone decided to create 13 quilts, alluding to the 13th Amendment and the original 13 colonies. They come up with pattern designs that are then digitized. The next step is to determine what people they want to represent on the matchbooks which are manufactured in the conventional way. The matchbooks are then sewn with crochet thread onto a felt backing. Finished dimensions are about eight feet square.

“We wanted to create a quilt you might have on your own bed,” says Norsworthy. “There are about 3,000 matchbooks on one quilt. As we were creating this object we realized it was starting to become heavy and we had to find an apparatus to hold it. They are being shown in galleries and the work is for sale. As they are going to collectors, we are helping them to figure out how to store them. It’s been both challenging and fun. We were originally hanging them but they can also be draped and then they take on a sculptural aspect. We love that collectors can show them as they choose.”

While the quilts appear decorative and are testimony to Norsworthy and Anthone’s talent and creativity, they convey symbolism and messaging and introduce a difficult conversation since the elements represent victims who have been killed.

In addition to creating the art, the two men have conducted workshops in public schools.

“Kids know a lot,” says Anthone. “We go as deep as we feel they can go. The children bring their ideas and contemporary thoughts as to what they see in the artwork. It feeds us (and makes us) feel that we are making an impact.

“We don’t see it as teaching but as part of our art practice. We hope they leave in a meaningful changed way and better understand the language of symbols. The children learn another means of communication, to empathize with people who are experiencing these injustices. They can express what they’ve learned with their own symbols—another form of language.”